Management Time: Who’s Got the Monkey?

Who’s Got The Monkey

I would love to take credit for this article, but I can’t! It was written by William Oncken, Jr. and Donald L. Wass for the Harvard Business Review in 1974.

I was first introduced to it by a legal colleague, Chris Corney, a solicitor and fellow head of department in a law firm that we both worked at. When I was first appointed to head the department, he printed off the article and told me to go somewhere quiet and read it, then read it again, until I completely understood the message the author was getting across.

I did as suggested, and it was some of the best advice I have ever received. So good, in fact, that I frequently share it with my own clients, whom I coach as leaders and managers. After my clients read it, we then consider their interpretation of the content, how it applies to them, and how they can apply the lessons to their own lives.

Note: This article was originally published in the November–December 1974 issue of HBR and has been one of the publication’s two best-selling reprints ever.

The Harvard Business Review asked Stephen R. Covey to provide a commentary for its reissue as a Classic.

Why do managers typically run out of time while their subordinates typically run out of work? Here, we shall explore the meaning of management time as it relates to the interaction between managers and their bosses, their peers, and their subordinates.

Specifically, we shall deal with three kinds of management time:

Boss-imposed time—is used to accomplish those activities that the boss requires and that the manager cannot disregard without direct and swift penalty.

System-imposed time—used to accommodate requests from peers for active support. Neglecting these requests will also result in penalties, though not always as direct or swift.

Self-imposed time—used to do things the manager originates or agrees to do. However, a particular portion of this kind of time will be taken by subordinates and is called subordinate-imposed time. The remaining portion will be the manager’s own, called discretionary time. Self-imposed time is not subject to penalty since neither the boss nor the system can discipline the manager for not doing what they didn’t know he had intended to do in the first place.

To accommodate those demands, managers need to control the timing and the content of what they do. Since what their bosses and the system imposed on them are subject to penalties, managers cannot tamper with those requirements. Thus, their self-imposed time becomes a significant area of concern.

Managers should try to increase the discretionary component of their self-imposed time by minimizing or eliminating the subordinate component. They will then use the added increment to get better control over their boss-imposed and system-imposed activities. Most managers spend much more time dealing with subordinates’ problems than they even faintly realize. Hence, we shall use the monkey-on-the-back metaphor to examine how subordinate-imposed time comes into being and what the superior can do about it.

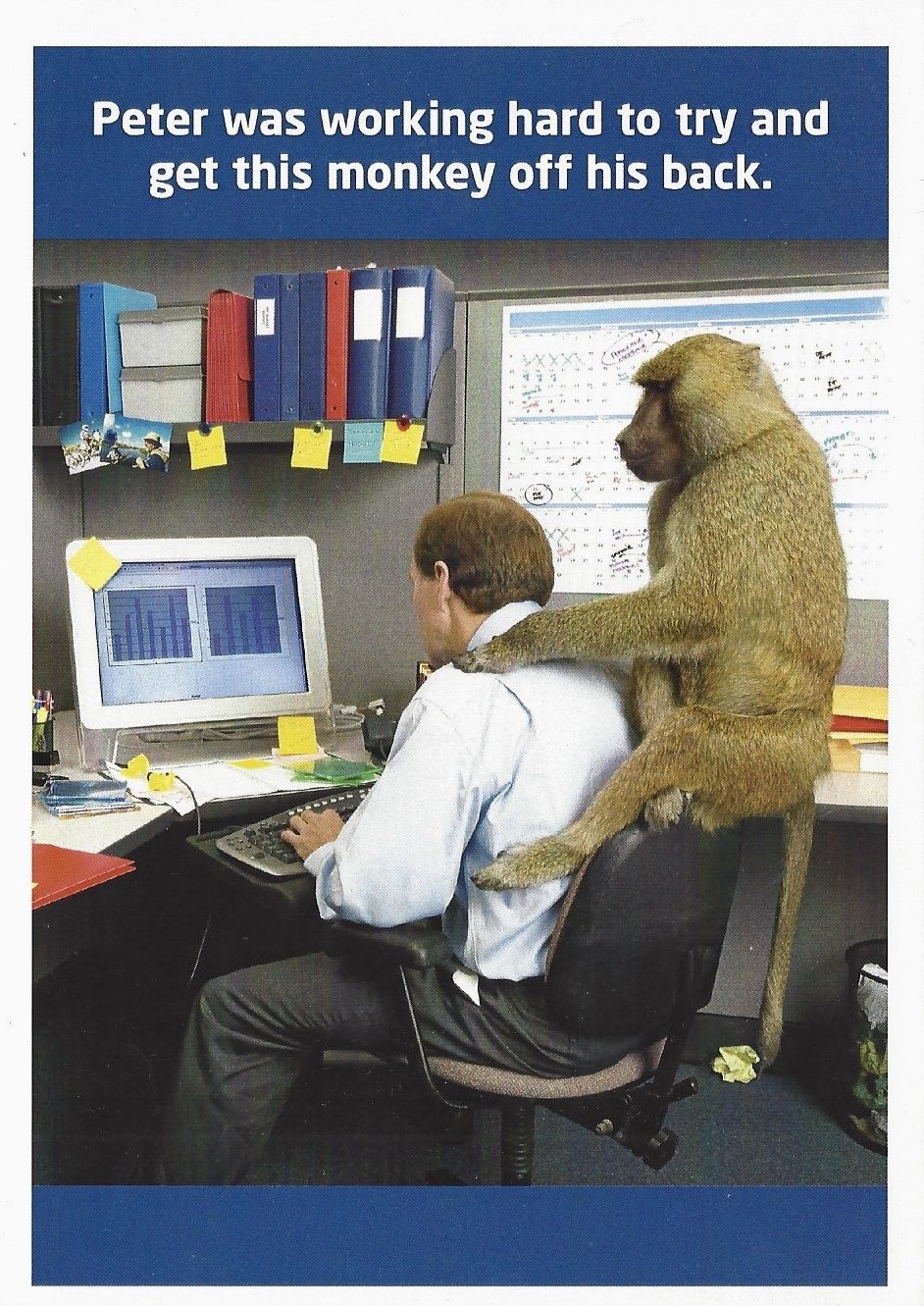

The author, Peter Gourri, with literally, a monkey on his back!

Where Is the Monkey?

Let us imagine a manager walking down the hall and noticing one of his subordinates, Jones, coming his way. When the two meet, Jones greets the manager, “Good morning. By the way, we’ve got a problem. You see….” As Jones continues, the manager recognizes in this problem the two characteristics common to all of the issues his subordinates gratuitously bring to his attention. Namely, the manager knows (a) enough to get involved but (b) not enough to make the on-the-spot expected decision. Eventually, the manager says, “So glad you brought this up. I’m in a rush right now. Meanwhile, let me think about it, and I’ll let you know.” Then he and Jones part company.

Let us analyze what just happened. Before they met, on whose back was the “monkey”? The subordinates. After they parted, on whose back was it? The managers. Subordinate-imposed time begins the moment a monkey successfully leaps from the back of a subordinate to the back of his or her superior and does not end until the monkey is returned to its proper owner for care and feeding. In accepting the monkey, the manager has voluntarily assumed a position subordinate to his subordinate. He has allowed Jones to make him her subordinate by doing two things a subordinate is generally expected to do for a boss—the manager has accepted a responsibility from his subordinate,. The manager has promised her a progress report.

The subordinate, to make sure the manager does not miss this point, will later stick her head in the manager’s office and cheerily query, “How’s it coming?” (This is called supervision.)

Or, let us imagine that after a conference with Johnson, another subordinate, the manager’s parting words are, “Fine. Send me a memo on that.”

Let us analyze this one. The monkey is now on the subordinate’s back because the next move is his, but it is poised for a leap. Watch that monkey. Johnson dutifully writes the requested memo and drops it in his out-basket. Shortly thereafter, the manager plucks it from his in-basket and reads it. Whose move is it now? The managers. If he does not make that move soon, he will get a follow-up memo from the subordinate. (This is another form of supervision.) The longer the manager delays, the more frustrated the subordinate will become (spinning his wheels) and the more guilty the manager will feel (his backlog of subordinate-imposed time will mount).

Or suppose once again that at a meeting with a third subordinate, Smith, the manager agrees to provide all the necessary backing for a public relations proposal he has just asked Smith to develop. The manager’s parting words to her are, “Just let me know how I can help.”

FURTHER READING

Now, let us analyze this. Again, the monkey is initially on the subordinate’s back. But for how long? Smith realizes that she cannot let the manager “know” until her proposal has the manager’s approval. And from experience, she also realizes that her proposal will likely sit in the manager’s briefcase for weeks before he eventually gets to it. Who’s got the monkey? Who will be checking up on whom? Wheel spinning and bottlenecking are well on their way again.

A fourth subordinate, Reed, has just been transferred from another part of the company so that he can launch and eventually manage a newly created business venture. The manager has said they should get together soon to hammer out a set of objectives for the new job, adding, “I will draw up an initial draft for discussion with you.”

Let us analyze this one, too. The subordinate has the new job (by formal assignment) and the full responsibility (by formal delegation), but the manager has the next move. Until he makes it, he will have the monkey, and the subordinate will be immobilized.

Why does all of this happen? In each instance, the manager and the subordinate assume at the outset, wittingly or unwittingly, that the matter under consideration is a joint problem. In each case, the monkey begins its career astride both their backs. All it has to do is move the wrong leg, and—presto! —the subordinate deftly disappears. The manager is thus left with another acquisition for his menagerie. Of course, monkeys can be trained not to move the wrong leg. But it is easier to prevent them from straddling backs in the first place.

Who Is Working for Whom?

Let us suppose that these same four subordinates are so thoughtful and considerate of their superior’s time that they take pains to allow no more than three monkeys to leap from each of their backs to his on any one day. In a five-day week, the manager will have picked up 60 screaming monkeys—far too many to do anything about them individually. So, he spends his subordinate-imposed time juggling his “priorities.”

Late Friday afternoon, the manager is in his office with the door closed for privacy so he can contemplate the situation while his subordinates are waiting outside to get their last chance before the weekend to remind him that he will have to “fish or cut bait.” Imagine what they are saying to one another about the manager as they wait: “What a bottleneck. He can’t make up his mind. How anyone ever got that high up in our company without being able to make a decision, we’ll never know.”

Worst of all, the manager cannot make any of these “next moves” because his time is almost entirely eaten up by meeting his own boss-imposed and system-imposed requirements. To control those tasks, he needs discretionary time, which, in turn, is denied to him when he is preoccupied with all these monkeys. The manager is caught in a vicious circle. But time is a-wasting (an understatement). The manager calls his secretary on the intercom and instructs her to tell his subordinates that he won’t be able to see them until Monday morning. At 7 pm, he drives home, intending with a firm resolve to return to the office tomorrow to get caught up over the weekend. He returns bright and early the next day only to see a foursome on the nearest green of the golf course across from his office window. Guess who?

That does it. He now knows who is working for whom. Moreover, he now sees that if he accomplishes during this weekend what he came to perform, his subordinates’ morale will go up so sharply that they will each raise the limit on the number of monkeys they will let jump from their backs to his. In short, with the clarity of a revelation on a mountaintop, he now sees that the more he gets caught up, the more he will fall behind.

With the clarity of a revelation on a mountaintop, the manager can now see that the more he gets caught up, the more he will fall behind.

He leaves the office at the speed of someone running away from a plague. His plan? To get caught up on something he hasn’t had time for in years: a weekend with his family. (This is one of the many varieties of discretionary time.)

Sunday night, he enjoys ten hours of sweet, untroubled slumber because he has clear-cut plans for Monday. He is going to get rid of his subordinate-imposed time. In exchange, he will get an equal amount of discretionary time, part of which he will spend with his subordinates to ensure that they learn the difficult but rewarding managerial art called “The Care and Feeding of Monkeys.”

The manager will also have plenty of discretionary time left over to control the timing and content of his boss-imposed time and his system-imposed time. It may take months, but the rewards will be enormous compared to how things have been. His ultimate objective is to manage his time.

Getting Rid of the Monkeys

The manager returns to the office Monday morning just late enough so that his four subordinates have collected outside his office waiting to see him about their monkeys. He calls them in one by one. The purpose of each interview is to take a monkey, place it on the desk between them, and figure out together how the next move might conceivably be the subordinates for certain monkeys that will take some doing. The subordinate’s next move may be so elusive that the manager may decide—just for now—merely to let the monkey sleep on the subordinate’s back overnight and have him or her return with it at an appointed time the following day to continue the joint quest for a more substantive move by the subordinate. (Monkeys sleep just as soundly overnight on subordinates’ backs as they do on superiors.)

As each subordinate leaves the office, the manager is rewarded with the sight of a monkey leaving his office on the subordinate’s back. For the next 24 hours, the subordinate will not be waiting for the manager; instead, the manager will be waiting for the subordinate.

Later, as if to remind himself that there is no law against his engaging in a constructive exercise in the interim, the manager strolls by the subordinate’s office, sticks his head in the door, and cheerily asks, “How’s it coming?” (The time consumed in doing this is discretionary for the manager and the boss imposed on the subordinate.)

In accepting the monkey, the manager has voluntarily assumed a position subordinate to his subordinate.

When the subordinate (with the monkey on his or her back) and the manager meet at the appointed hour the next day, the manager explains the ground rules in words to this effect:

“At no time while I am helping you with this or any other problem will your problem become mine. The instant your problem becomes mine, you no longer have a problem. I cannot help a person who hasn’t got a problem.

“When this meeting is over, the problem will leave this office precisely as it came in—on your back. You may ask for my help at any appointed time, and we will determine what the next move will be and which of us will make it.

“In those rare instances where the next move turns out to be mine, you and I will determine it together. I will not make any move alone.”

The manager follows this same line of thought with each subordinate until about 11 a.m. when he realizes he doesn’t have to close his door. His monkeys are gone. They will return—but by appointment only. His calendar will ensure this.

Transferring the Initiative

What we have been driving at in this monkey-on-the-back analogy is that managers can transfer initiative back to their subordinates and keep it there. We have tried to highlight a truism as obvious as it is subtle: namely, before developing initiative in subordinates, the manager must see to it that they have the initiative. Once the manager takes it back, he will no longer have it and can kiss his discretionary time goodbye. It will all revert to subordinate-imposed time.

Nor can the manager and the subordinate effectively have the same initiative simultaneously. The opener, “Boss, we’ve got a problem,” implies this duality and represents, as noted earlier, a monkey astride two backs, which is the wrong way to start a monkey’s career. Let us, therefore, take a few moments to examine what we call “The Anatomy of Managerial Initiative.”

There are five degrees of initiative that the manager can exercise concerning the boss and the system:

1. wait until told (lowest initiative);

2. ask what to do;

3. recommend, then take resulting action;

4. act, but advise at once;

5. and act independently, then routinely report (highest initiative).

Clearly, the manager should be professional enough not to indulge in initiatives 1 and 2 related to the boss or the system. A manager who uses initiative 1 has no control over either the timing or the content of boss-imposed or system-imposed time, thereby forfeiting any right to complain about what he or she is told to do or when. The manager who uses Initiative 2 controls the timing but not the content. Initiatives 3, 4, and 5 leave the manager in control of both, with the most significant control being exercised at level 5.

Concerning subordinates, the manager’s job is twofold. First, to outlaw initiatives 1 and 2, thus giving subordinates no choice but to learn and master “Completed Staff Work.” Second, to see that for each problem leaving his or her office, an agreed-upon level of initiative is assigned to it, in addition to an agreed-upon time and place for the next manager-subordinate conference. The latter should be duly noted on the manager’s calendar.

The Care and Feeding of Monkeys

To further clarify our analogy between the monkey on the back and the processes of assigning and controlling, we shall refer briefly to the manager’s appointment schedule, which calls for five hard-and-fast rules governing the “Care and Feeding of Monkeys.” (Violation of these rules will cost discretionary time.)

Rule 1.

Monkeys should be fed or shot. Otherwise, they will starve to death, and the manager will waste valuable time on postmortems or attempted resurrections.

Rule 2.

The monkey population should be kept below the maximum number the manager has time to feed. Subordinates will find time to work as many monkeys as he or she finds time to feed, but no more. Feeding an adequately maintained monkey shouldn’t take more than five to 15 minutes.

Rule 3.

Monkeys should be fed by appointment only. The manager should not have to hunt down starving monkeys and feed them on a catch-as-catch-can basis.

Rule 4.

Monkeys should be fed face-to-face or by telephone, but never by mail. (Remember—with mail, the next move will be the managers.) Documentation may add to the feeding process but cannot replace feeding.

Rule 5.

Every monkey should be assigned the next feeding time and degree of initiative. These may be revised by mutual consent but are never allowed to become vague or indefinite. Otherwise, the monkey will starve or wind up on the manager’s back.

Making Time for Gorillas

by Stephen R. Covey When Bill Oncken wrote this article in 1974, managers were in a terrible bind. They were ...

“Get control over the timing and content of what you do” is appropriate advice for managing time. The first order of business is for the manager to enlarge his or her discretionary time by eliminating subordinate-imposed time. The second is for the manager to use a portion of this newfound discretionary time to see that each subordinate has the initiative and applies it. The third is for the manager to use another portion of the increased discretionary time to get and keep control of the timing and content of both boss-imposed and system-imposed time. All these steps will increase the manager’s leverage and enable the value of each hour spent managing management time to multiply without a theoretical limit.

Do You Have the Skills You Need to Be the Boss?

Do You Have the Skills You Need to Be the Boss?

Transitioning into management for the first time can be a significant career milestone for many people. Identifying which skills you might need to develop before leaping will be helpful for any potential leadership shift. Ask yourself these five questions:

Transitioning into management for the first time can be a significant career milestone for many people. Identifying which skills you might need to develop before leaping will be helpful for any potential leadership shift. Ask yourself these five questions:

• What’s my leadership style? Reflect on your strengths, personality, and values, then decide what you want to be known for. Remember, you can adapt your approach over time as you continue to learn and advance.

• How will I help my team grow? Understanding how to measure performance and assess gaps and growth opportunities on your team will be essential in your role as a manager. Take time to think about how your promotion may impact team structures and dynamics.

• How will I prioritize and delegate work effectively? Ask yourself what you’d need to stop doing, keep doing, and do more of—and how you’ll provide oversight and accountability for the work you assign to others.

• Am I an excellent public speaker, and can I lead meetings? Do an honest appraisal of your communication skills and assess your comfort with leading meetings and presenting to larger groups.

• Am I comfortable delivering feedback and resolving conflict? Providing helpful direction, addressing performance gaps, and solving interpersonal problems are essential managerial responsibilities. Consider issues you may have witnessed with coworkers regarding processes, projects, or interpersonal dynamics. What did you learn from what you observed?

What to do if you hear or become aware of a microaggression

All leaders, whether holding the title of manager, director, supervisor, department head, partner or more importantly, an individual in the workplace, have a unique opportunity, as well as a responsibility to be a role model in creating an inclusive workplace.

All leaders, whether holding the title of manager, director, supervisor, department head, partner or more importantly, an individual in the workplace, have a unique opportunity, as well as a responsibility to be a role model in creating an inclusive workplace.

What this means in real terms is recognizing and mitigating potential harmful behaviors in yourself, and in your team members. Easily one of the main examples of this is speaking up if you hear or see something inappropriate, especially any act which could be considered a microaggression, such as interrupting, taking up airtime, dismissing or taking credit for someone else’s ideas, diminishing someone’s experience, stereotyping, or using problematic language. These behaviors are often unintentional, which makes it all the more important to call them out. If a situation like this comes up, be sure to pause and name what’s just happened. For example, if someone uses an outdated or problematic word to describe a group of people, you might say: “Hey, Just so we are all aware, I just want to take a moment here. It’s really important to focus on the language we use to describe people, and XYZ is a not considered an acceptable term.” The object of the exercise is to educate others rather than shame them (which is more likely to alienate and less likely to result in change).

It is always good practice to follow up with the individual after the incident to discuss in private and provide them with helpful learning resources, offering to continue the conversation if they’d find it helpful. The world can be a complicated ever-changing place where people might not fully understand their conduct. It isn’t wrong to take a moment to hold someone to account or support them with knowledge.

This article is not intended to address the specific definitions of microaggressions themselves but this helpful video from Quart while not comprehensive is a helpful guide.