“I Quit”—Written on Toilet Paper: A Harsh Reminder for Leaders

It’s the kind of thing you’d think was a joke on social media—until it lands on your desk. A resignation written on toilet paper.

The message? “I’ve chosen this type of paper as a symbol of how this company has treated me.”

Painful. Poignant. Preventable.

In my work as an executive coach to lawyers, executives, and business owners, I’ve learned this: People don’t leave jobs. They leave their cultures.

And too often, they leave without saying a word—until the damage is done.

Here’s how to avoid losing your best employees:

It’s the kind of thing you’d think was a joke on social media—until it lands on your desk. A resignation written on toilet paper.

The message? “I’ve chosen this type of paper as a symbol of how this company has treated me.”

Painful. Poignant. Preventable.

In my work as an executive coach to lawyers, executives, and business owners, I’ve learned this: People don’t leave jobs. They leave their cultures.

And too often, they leave without saying a word—until the damage is done.

Here’s how to avoid losing your best employees:

1. Your culture speaks louder than your strategy.

Mission statements and value posters are meaningless if daily behaviors don’t reflect them. Culture is how people feel at work. Do they feel safe to speak up? Respected? Heard?

2. Your managers make or break trust.

The number one reason people leave? Poor management. Invest in developing your team leaders. Give them the coaching, tools, and feedback to lead well—not just manage output.

3. Recognition is not optional.

High performers won’t beg to be seen. If their effort is consistently ignored, they’ll move on quietly, often to your competitor.

4. Exit interviews come too late.

Schedule stay interviews instead. Understand what motivates your top people—and what might drive them away.

5. Don’t wait for dramatic exits to pay attention.

When someone metaphorically (or literally) uses toilet paper to resign, it’s already too late. But their message is worth listening to.

Leadership starts with awareness and builds through action. If you’re serious about retaining talent, it’s time to lead like it.

National Small Business Week: The Quiet Power of Executive Coaching

National Small Business Week: The Quiet Power of Executive Coaching

Small businesses are the heartbeat of the economy—but they’re also under pressure like never before.

This National Small Business Week, I want to shine a light on the challenges small business owners face—and how coaching can offer real, practical support.

Small businesses are the heartbeat of the economy, but they’re also under pressure like never before.

This National Small Business Week, I want to highlight the challenges small business owners face and how coaching can offer real, practical support.

As a former lawyer turned executive coach, I’ve worked with business owners across industries. What do they all share? A need for:

• Stability in unstable markets

• Leadership habits that last

• Strategic direction for scaling

• Space to think, grow, and breathe

Coaching is not about giving you more to do. It’s about helping you do the right things—faster, smarter, and with more impact.

Through personalized coaching, we tackle:

✅ Your leadership blind spots

✅ Your team challenges

✅ Your decision fatigue

✅ Your strategic goals

And we do it with clarity, accountability, and respect for your time.

This week, celebrate your grit.

Next week, let’s talk about your growth.

National Law Day: From London Outdoor Clerk to New York Executive Coach

National Law Day: From London Outdoor Clerk to New York Executive Coach

That grainy photo from the early 1990s? That was me—trying to look important. I was a young lawyer, learning quickly, working hard, and proud to be part of something that mattered.

My journey began at One King’s Bench Walk, Inner Temple, London, in 1987 as an Outdoor Clerk. I spent those early days observing, running documents between courts, and soaking up every bit of experience I could.

National Law Day: From Outdoor Clerk to Executive Coach

That grainy photo from the early 1990s? That was me, trying to look important. I was a young lawyer, learning quickly, working hard, and proud to be part of something that mattered.

My journey began in 1987 as an outdoor clerk at One King’s Bench Walk, Inner Temple, London. I spent those early days observing, running documents between courts, and soaking up every bit of experience I could.

Eventually, I became a Senior Commercial Litigation Lawyer. I handled disputes of all shapes and sizes—from the County Court Small Claims Track to the European Court of Justice.

In 2016, I moved to the United States and worked in-house in Manhattan.

But what mattered most to me wasn’t the case law or the court hierarchy. It was the relationships.

I have helped large corporations and small business owners. I have always believed that the size of the client doesn’t determine the importance of the case because trust, care, and clarity matter at every level.

Law gave me an opportunity to serve.

Today, as an executive coach, I draw from that deep well of legal experience to support lawyers, executives, and business owners navigating their own challenges.

On National Law Day, I’m grateful for the profession that shaped me and still inspires how I lead and coach.

May Is Mental Health Awareness Month—Let’s Make It Mean Something

May Is Mental Health Awareness Month—Let’s Make It Mean Something

Mental health awareness isn’t a seasonal trend. It’s a leadership priority.

As a coach to lawyers, executives, and business owners, I see it constantly: driven professionals who are exhausted, anxious, and emotionally depleted—but afraid to talk about it.

The culture of high achievement often rewards stress and burnout. But the truth is, you can’t lead well if your mind isn’t well.

Mental health awareness isn’t a seasonal trend. It’s a leadership priority.

As a coach to lawyers, executives, and business owners, I see it constantly: driven professionals who are exhausted, anxious, and emotionally depleted—but afraid to talk about it.

The culture of high achievement often rewards stress and burnout. But the truth is, you can’t lead well if your mind isn’t well.

This month is an opportunity—not just to raise awareness, but to rethink how we approach performance, energy, and resilience.

Here’s how to lead with mental health in mind:

🧠 Set boundaries—and stick to them.

Not every call is urgent. Not every email needs a midnight reply.

🗣 Talk openly about emotional fatigue.

When leaders normalize these conversations, teams become safer, healthier, and more productive.

📆 Build in breaks, just as you would in meetings.

Protecting your schedule is protecting your performance.

🌱 Engage in daily renewal.

Meditation, exercise, sleep, journaling—whatever helps you reset.

Leadership is not about being unbreakable. It’s about knowing how to reset, recharge, and return stronger.

Let’s make this May a turning point—for ourselves, our teams, and our culture.

Protect Your Team from Strategy Fatigue

You’ve seen it: your people aren’t lazy or disengaged—they’re overwhelmed. They’re suffering from strategy fatigue.

It happens when:

• Everything becomes a priority

• New ideas flood in weekly

• Direction keeps changing without clarity

The result? Confusion. Burnout. Paralysis.

You’ve seen it: your people aren’t lazy or disengaged—they’re overwhelmed. They’re suffering from strategy fatigue.

It happens when:

• Everything becomes a priority

• New ideas flood in weekly

• Direction keeps changing without clarity

The result? Confusion. Burnout. Paralysis.

Your team wants to execute. But they need to focus. Here’s how to deliver it:

1. Set Screening Criteria

Define what fits your strategic goals—and what doesn’t. Create clear thresholds that every new idea must pass. If it doesn’t align? Say no or defer it.

2. Use Scoring Tools

Adopt a value vs. effort matrix or weighted scoring model. Ground your decisions in logic, not passion. This adds clarity, fairness, and consistency.

3. Test Before Committing

Every idea doesn’t require full resources upfront. Run a proof-of-concept. Small, focused tests reduce risk and validate assumptions.

4. Create a Single Visible Pipeline

List every non-routine initiative in one place. Review it regularly. Spot duplication, overload, or distractions. Apply the “one in, one out” rule.

Final Thought

Your team’s capacity is one of your most precious assets. Protect it. Strategy is only as strong as your ability to deliver.

Clarity is the new leadership currency. Spend it wisely.

Why Asset Protection Is a Leadership Essential: Lessons from the NC-CBA Event

Why Asset Protection Is a Leadership Essential: Lessons from the NC-CBA Event

Building a business is hard work. Protecting it should be just as intentional.

This week, I had the privilege of attending the monthly networking event hosted by the North Carolina Chinese Business Association (NC-CBA), featuring an outstanding talk by Fiona Wang of Wang Law Firm.

Why Asset Protection Is a Leadership Essential: Lessons from the NC-CBA Event

Building a business is hard work. Protecting it should be just as intentional.

This week, I had the privilege of attending the monthly networking event hosted by the North Carolina Chinese Business Association (NC-CBA), featuring an outstanding talk by Fiona Wang of Wang Law Firm.

Fiona delivered an important reminder: proactive asset protection is critical for business owners and entrepreneurs.

It’s not enough to focus on growth. We must also focus on safeguarding what we’re building.

Key insights from the session:

🔹 Protecting personal and business assets is non-negotiable.

🔹 Smart legal structures matter at every stage of business growth.

🔹 Resilience isn’t reactive—it’s built intentionally.

It was also a real pleasure to meet members of the RTP Chinese business community. As someone who worked with Chinese businesses in the UK and China during my legal career in London, it reminded me of the powerful role global partnerships play in business success.

Protect your future. Build your resilience. That’s leadership.

From Fear to Flow: Highlights from XPX Triangle’s Networking Lunch & Learn

On April 17th, I had the privilege of leading a Lunch & Learn for XPX Triangle at Milton’s Pizza & Pasta in Raleigh. The session, “The Art & Strategy of Networking,” was designed to help professionals reframe how they approach in-person networking—from fear and awkwardness to structure, confidence, and results.

On April 17th, I had the privilege of leading a Lunch & Learn for XPX Triangle at Milton’s Pizza & Pasta in Raleigh. The session, “The Art & Strategy of Networking,” was designed to help professionals reframe how they approach in-person networking—from fear and awkwardness to structure, confidence, and results.

The group was phenomenal—open, curious, and highly engaged. We dove into:

• The common survival mechanisms that hinder networking success

• How structure and small wins create confidence

• Why your goal should be to connect, not perform

• How to re-enter conversations, move with intention, and follow up meaningfully

Attendees were also given two valuable tools:

1. My presentation: From Fear to Flow – Mastering the Art of Networking

2. A free PDF copy of my book: 52 Rules to Work the Room

As I often say, “You are the asset. Design the room you walk into.”

If you’re interested in learning more about how to elevate your executive presence, boost team performance, or become a more powerful connector in your industry, let’s connect.

Thank you again to everyone who attended, and to XPX Triangle for the warm welcome.

Peter Gourri

Executive Coach | Author | Business Growth Strategist

28-Day Positivity Challenge

The 28 Days of Positivity Program aims to provide a focused, time-limited framework that helps individuals consciously shift their mindsets, habits, and behaviors toward a more optimistic, resilient, and growth-oriented lifestyle and work approach. It offers value both personally and professionally

The 28 Days of Positivity Program aims to provide a focused, time-limited framework that helps individuals consciously shift their mindsets, habits, and behaviors toward a more optimistic, resilient, and growth-oriented lifestyle and work approach. It offers value both personally and professionally by:

🔹 1. Resetting Default Thinking Patterns

Many high performers, particularly in demanding roles, find themselves caught in reactive or critical thinking loops. A structured 28-day approach provides the opportunity to break these patterns and substitute them with intentional, constructive alternatives.

🔹 2. Building Psychological Fitness

Just like physical health, emotional resilience needs regular practice. Daily positive prompts aid in strengthening:

• Self-awareness

• Emotional regulation

• Gratitude

• Optimism

• Empathy

These principles are essential for leadership, teamwork, and decision-making.

🔹 3. Develop Sustainable Micro-Habits

Significant transformations often begin with small, daily actions. The program employs micro-shifts—5 to 10-minute practices—that gradually evolve into lasting changes in mindset, relationships, and communication style.

🔹 4. Reconnect with Purpose and People

Participants are encouraged to reflect on values, recognize what is effective, and strengthen their human connections at work and home. This enhances morale, engagement, and trust.

🔹 5. Create Momentum for Change

Twenty-eight days is long enough to create a meaningful impact but short enough to feel manageable. It is designed to catalyze longer-term shifts in:

• Personal outlook

• Team culture

• Organizational energy

It serves as the springboard for more consistent well-being and productivity practices.

Who It’s For:

• Individuals feeling stretched, negative, or stuck

• Teams looking to improve morale and cohesion

• Leaders wanting to boost engagement and emotional intelligence

• Anyone seeking to live and lead with more clarity, calm, and connection

Here are my suggestions for 28 days

Week 1: Foundations of Positive Awareness

Day 1 – Set Your Intention

Write down why you’re doing this. Who do you want to be in 28 days?

Day 2 – Three Good Things

Before bed, list three good things that happened today and why they mattered.

Day 3 – Positive Self-Talk Audit

Pay attention to your inner critic today. Jot down three instances when you transformed a negative thought into a positive one.

Day 4 – Gratitude Note

Send a thank-you message or letter to someone who has positively impacted your life.

Day 5 – Move with Joy

Engage in 20 to 30 minutes of movement- such as walking, stretching, or dancing- while reflecting on what feels good about being alive.

Day 6 – Kindness Act

Perform an unexpected act of kindness for someone else. Observe how it influences your mood.

Day 7 – Digital Detox Hour

Turn off devices for one hour. Be present. Write in your journal about how it made you feel.

Week 2: Rewiring Through Routine

Day 8 – Morning Positivity Primer

Start your day with a 5-minute gratitude or affirmation practice.

Day 9 – The Compliment Challenge

Offer five sincere compliments today. Consider how this alters interactions.

Day 10 – Nature Reset

Spend over 15 minutes in nature. Observe, breathe, and absorb. Write down your observations.

Day 11 – Celebrate a Small Win

Identify one small win today and celebrate it—out loud.

Day 12 – Positive Reflection

Reflect on a challenging moment from your past. What strength did it cultivate within you?

Day 13 – Smile on Purpose

Smile at everyone you encounter today. Observe the ripple effect.

Day 14 – Declutter One Space

Clear out a drawer, a desk, or your inbox. Observe how physical space influences mental space.

Week 3: Cultivating Positivity in Relationships

Day 15 – Forgiveness Practice

Compose (but don’t send) a letter of forgiveness to someone who has hurt you. Release it.

Day 16 – Lift Someone Up

Contact someone to express how they’ve positively influenced you.

Day 17 – Listen Deeply

Engage in one conversation today with the sole goal of listening without trying to fix or judge.

Day 18 – Social Media Detox

Unfollow or mute accounts that regularly drain or annoy you.

Day 19 – Share Your Joy

Share, discuss, or express something that truly brings you joy—without feeling the need to apologize for it.

Day 20 – Family Gratitude Circle

Gather those you live with and have everyone share one thing they appreciate about each other.

Day 21 – Write Your Future Self a Letter

Imagine yourself thriving six months from now. What does that version of you want you to understand today?

Week 4: Sustaining and Spreading Positivity

Day 22 – Affirmation Reboot

Create three affirmations that resonate with you and inspire motivation. Recite them throughout the day.

Day 23 – Mindful Breathing Break

Take three intentional breathing breaks today. Just pause, inhale, exhale, and reset.

Day 24 – Highlight Reel

Reflect on your journal or notes from the past three weeks. What themes stand out to you? What surprised you?

Day 25 – Support Someone’s Dream

Inquire about someone's dream and suggest a small way you can offer support or encouragement.

Day 26 – Celebrate Your Growth

List five things you’ve learned, felt, or changed through this process.

Day 27 – Revisit Your Why

Reflect on Day 1’s intention. How have you honored it? What do you wish to continue?

Day 28 – The Ripple Effect

Consider three ways to keep spreading positivity—at home, at work, and in your community. Take action on one today.

Good Luck, and enjoy your newfound outlook!

5 Years After COVID — Leadership Lessons That Still Matter.

5 Years After COVID — Leadership Lessons That Still Matter

It’s been five years since COVID-19 upended our lives, but its impact still shapes how we live and lead. For me, that lesson is personal.

In the middle of the pandemic, I found myself on the floor of my bathroom in Jersey City, New Jersey, battling what I initially believed was moderate COVID-19. I later learned it was a profound and serious case. I was hallucinating, feverish, and calling out for my long-deceased mother — a desperate instinct when I felt powerless.

Recovery took months, and while I was fortunate to survive, the aftermath lingered. I later sustained spinal and neck injuries from a car accident while returning from my first vaccination. Despite these setbacks, I know I was one of the lucky ones — too many others didn’t make it.

COVID changed more than our health — it reshaped leadership itself. Disruption is no longer the exception; it’s the new normal.

It’s been five years since COVID-19 upended our lives, but its impact still shapes how we live and lead. For me, that lesson is personal.

In the middle of the pandemic, I found myself on the floor of my bathroom in Jersey City, New Jersey, battling what I initially believed was moderate COVID-19. I later learned it was a profound and serious case. I was hallucinating, feverish, and calling out for my long-deceased mother — a desperate instinct when I felt powerless.

Recovery took months, and while I was fortunate to survive, the aftermath lingered. I later sustained spinal and neck injuries from a car accident while returning from my first vaccination. Despite these setbacks, I know I was one of the lucky ones — too many others didn’t make it.

COVID changed more than our health — it reshaped leadership itself. Disruption is no longer the exception; it’s the new normal.

5 Key Lessons for Leaders in an Unpredictable World

Here’s what I’ve learned — and now teach — about leading through uncertainty:

1. Embrace Uncertainty Proactively

Instead of relying on rigid annual plans, focus on continuous scenario forecasting. Leaders who anticipate change — instead of reacting to it — gain an advantage. Build flexible teams that can pivot quickly.

2. Focus on Performance Over Presence

The pandemic proved that performance isn’t tied to office attendance. Focus on outcomes, not hours spent in the office. Design hybrid models that balance employee engagement with business objectives, and reinforce accountability with clear goals — not rigid mandates.

3. Test New Ideas — Fast

In times of disruption, waiting for a perfect plan is dangerous. Adopt a mindset of small experiments — launch pilot projects, gather insights, and adapt rapidly. Innovation thrives in cultures where experimentation is encouraged.

4. Make Decisions with Limited Information

Crisis rarely offers perfect data. Leaders who excel develop frameworks for confident decision-making in imperfect conditions. Set guiding principles for decisions and adjust as new insights develop.

5. Communicate with Authenticity

In uncertain moments, people crave honest communication. Transparency builds trust — and trust stabilizes teams. Acknowledge what you don’t know, commit to what you do know, and ensure your actions align with your message.

Adapting for the Future

The world will continue to change — whether through economic shifts, technological advances, or unexpected crises. Leadership success now hinges on adaptability, resilience, and a willingness to embrace change.

The leaders who thrive will be those who develop the mindset, skills, and systems to navigate uncertainty.

What changes have you made to your leadership approach since the pandemic? If you’d like to explore strategies for enhancing adaptability, I’d be glad to help.

#Leadership #Resilience #ExecutiveCoaching #Adaptability

Celebrate Groundhog Day - Break the Cycle!

Today is Groundhog Day when a small and arguably cute creature will indicate whether we have an early spring or eight more weeks of winter! It has been proven, surprisingly, you might think, that the predictions have no scientific standing whatsoever and have been mainly incorrect……

Today is Groundhog Day when a small and arguably cute creature will indicate whether we have an early spring or eight more weeks of winter! It has been proven, surprisingly, you might think, that the predictions have no scientific standing whatsoever and have been mainly incorrect……

The day is also synonymous with the 1993 movie Groundhog Day, starring Bill Murray and Andie MacDowell. In the movie, Murray’s character relives his day over and over again! Sound familiar?

So, that takes me to the purpose of this post! My question is, what will you do to break your Groundhog Day? Are you prepared to step outside your comfort zone by taking a leap of faith and breaking the cycle to live a new and exciting life? Or is it easier to carry on in the same existence repeatedly…….

It’s your call! If you need help, email me. You might be surprised by how great life can be.

#groundhogday2019 #groundhogday #leapoffaith #comfortzone #living #lifecoachingworks #change #lifecoaching

Learning from past decisions!

Learning from past decisions that went wrong, from breadmaking to running businesses!

I’ve been making bread for the last year. This is something my fiancé started, and I have been working ever since to perfect and expand my skills in baking bread, scones, and various cakes. Sometimes I end up with a soggy bottom or an exploding loaf where I add too much or too little, but I “Persevere”, not just because that is my old school moto but because I have grown to recognize that does not go to plan in life is a failure. It is a learning experience to do better and easier next time.

Here are some I made earlier.......

Learning from past decisions that went wrong, from breadmaking to running businesses!

I’ve been making bread for the last year. My fiancé started this, and I have been working ever since to perfect and expand my skills in baking bread, scones, and various cakes. Sometimes, I end up with a soggy bottom or an exploding loaf where I add too much or too little, but I “persequere” not just because that is my old school moto but also because I have learned through experience to recognize that everything does not always go to plan in life. When it doesn’t, it is not a failure but a learning experience to do better and easier next time.

Of course, we can all fall into the trap of repeating the same actions repeatedly, hoping for different results the next time. Sticking to familiar patterns is easy, but our real growth comes from examining our past decisions and learning from them.

Ask yourself these questions to reflect on your past mistakes and make the right decision this time around.

What’s the decision I’m facing now? Clearly define the problem before jumping to a solution. A vague problem leads to an unclear path forward.

What’s stressful about this decision? Identify what’s making you anxious. Stress can cloud your judgment, pushing you to rely on habitual, biased thinking instead of exploring new options.

What past decisions can I learn from? Analyze past choices that didn’t work out. Pinpoint what went wrong and why. This helps you avoid repeating the same missteps this time around.

What assumptions led to those mistakes? Look back and challenge the assumptions you made. Were you relying on shortcuts or untested beliefs?

How can I apply this learning now? Use what you’ve uncovered to inform your current decisions, shifting your behavior and thought process for better outcomes.

These are small snippets to help you start your journey to success. Ask yourself how I can support you one-to-one to accomplish more professionally and personally. If you would like further assistance or guidance in this or other areas, such as setting strategic goals for yourself or your business, book an appointment with me using the link in the contact section so we can talk. You never know—it might just create a change in your future!

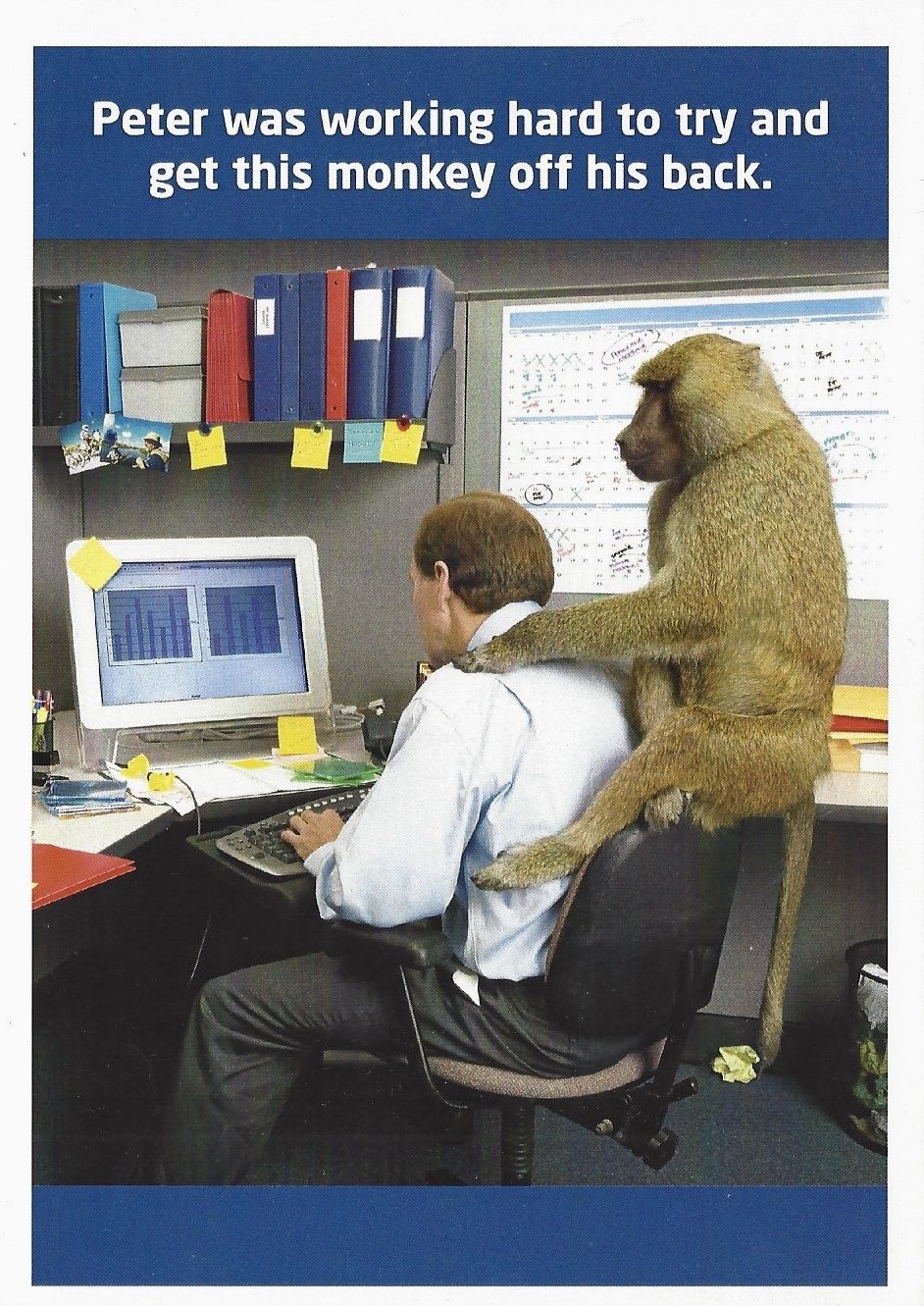

Management Time: Who’s Got the Monkey?

Who’s Got The Monkey

I would love to take credit for this article, but I can’t! It was written by William Oncken, Jr. and Donald L. Wass for the Harvard Business Review in 1974.

I was first introduced to it by a legal colleague, Chris Corney, a solicitor and fellow head of department in a law firm that we both worked at. When I was first appointed to head the department, he printed off the article and told me to go somewhere quiet and read it, then read it again, until I completely understood the message the author was getting across.

I did as suggested, and it was some of the best advice I have ever received. So good, in fact, that I frequently share it with my own clients, whom I coach as leaders and managers. After my clients read it, we then consider their interpretation of the content, how it applies to them, and how they can apply the lessons to their own lives.

Note: This article was originally published in the November–December 1974 issue of HBR and has been one of the publication’s two best-selling reprints ever.

The Harvard Business Review asked Stephen R. Covey to provide a commentary for its reissue as a Classic.

Why do managers typically run out of time while their subordinates typically run out of work? Here, we shall explore the meaning of management time as it relates to the interaction between managers and their bosses, their peers, and their subordinates.

Specifically, we shall deal with three kinds of management time:

Boss-imposed time—is used to accomplish those activities that the boss requires and that the manager cannot disregard without direct and swift penalty.

System-imposed time—used to accommodate requests from peers for active support. Neglecting these requests will also result in penalties, though not always as direct or swift.

Self-imposed time—used to do things the manager originates or agrees to do. However, a particular portion of this kind of time will be taken by subordinates and is called subordinate-imposed time. The remaining portion will be the manager’s own, called discretionary time. Self-imposed time is not subject to penalty since neither the boss nor the system can discipline the manager for not doing what they didn’t know he had intended to do in the first place.

To accommodate those demands, managers need to control the timing and the content of what they do. Since what their bosses and the system imposed on them are subject to penalties, managers cannot tamper with those requirements. Thus, their self-imposed time becomes a significant area of concern.

Managers should try to increase the discretionary component of their self-imposed time by minimizing or eliminating the subordinate component. They will then use the added increment to get better control over their boss-imposed and system-imposed activities. Most managers spend much more time dealing with subordinates’ problems than they even faintly realize. Hence, we shall use the monkey-on-the-back metaphor to examine how subordinate-imposed time comes into being and what the superior can do about it.

The author, Peter Gourri, with literally, a monkey on his back!

Where Is the Monkey?

Let us imagine a manager walking down the hall and noticing one of his subordinates, Jones, coming his way. When the two meet, Jones greets the manager, “Good morning. By the way, we’ve got a problem. You see….” As Jones continues, the manager recognizes in this problem the two characteristics common to all of the issues his subordinates gratuitously bring to his attention. Namely, the manager knows (a) enough to get involved but (b) not enough to make the on-the-spot expected decision. Eventually, the manager says, “So glad you brought this up. I’m in a rush right now. Meanwhile, let me think about it, and I’ll let you know.” Then he and Jones part company.

Let us analyze what just happened. Before they met, on whose back was the “monkey”? The subordinates. After they parted, on whose back was it? The managers. Subordinate-imposed time begins the moment a monkey successfully leaps from the back of a subordinate to the back of his or her superior and does not end until the monkey is returned to its proper owner for care and feeding. In accepting the monkey, the manager has voluntarily assumed a position subordinate to his subordinate. He has allowed Jones to make him her subordinate by doing two things a subordinate is generally expected to do for a boss—the manager has accepted a responsibility from his subordinate,. The manager has promised her a progress report.

The subordinate, to make sure the manager does not miss this point, will later stick her head in the manager’s office and cheerily query, “How’s it coming?” (This is called supervision.)

Or, let us imagine that after a conference with Johnson, another subordinate, the manager’s parting words are, “Fine. Send me a memo on that.”

Let us analyze this one. The monkey is now on the subordinate’s back because the next move is his, but it is poised for a leap. Watch that monkey. Johnson dutifully writes the requested memo and drops it in his out-basket. Shortly thereafter, the manager plucks it from his in-basket and reads it. Whose move is it now? The managers. If he does not make that move soon, he will get a follow-up memo from the subordinate. (This is another form of supervision.) The longer the manager delays, the more frustrated the subordinate will become (spinning his wheels) and the more guilty the manager will feel (his backlog of subordinate-imposed time will mount).

Or suppose once again that at a meeting with a third subordinate, Smith, the manager agrees to provide all the necessary backing for a public relations proposal he has just asked Smith to develop. The manager’s parting words to her are, “Just let me know how I can help.”

FURTHER READING

Now, let us analyze this. Again, the monkey is initially on the subordinate’s back. But for how long? Smith realizes that she cannot let the manager “know” until her proposal has the manager’s approval. And from experience, she also realizes that her proposal will likely sit in the manager’s briefcase for weeks before he eventually gets to it. Who’s got the monkey? Who will be checking up on whom? Wheel spinning and bottlenecking are well on their way again.

A fourth subordinate, Reed, has just been transferred from another part of the company so that he can launch and eventually manage a newly created business venture. The manager has said they should get together soon to hammer out a set of objectives for the new job, adding, “I will draw up an initial draft for discussion with you.”

Let us analyze this one, too. The subordinate has the new job (by formal assignment) and the full responsibility (by formal delegation), but the manager has the next move. Until he makes it, he will have the monkey, and the subordinate will be immobilized.

Why does all of this happen? In each instance, the manager and the subordinate assume at the outset, wittingly or unwittingly, that the matter under consideration is a joint problem. In each case, the monkey begins its career astride both their backs. All it has to do is move the wrong leg, and—presto! —the subordinate deftly disappears. The manager is thus left with another acquisition for his menagerie. Of course, monkeys can be trained not to move the wrong leg. But it is easier to prevent them from straddling backs in the first place.

Who Is Working for Whom?

Let us suppose that these same four subordinates are so thoughtful and considerate of their superior’s time that they take pains to allow no more than three monkeys to leap from each of their backs to his on any one day. In a five-day week, the manager will have picked up 60 screaming monkeys—far too many to do anything about them individually. So, he spends his subordinate-imposed time juggling his “priorities.”

Late Friday afternoon, the manager is in his office with the door closed for privacy so he can contemplate the situation while his subordinates are waiting outside to get their last chance before the weekend to remind him that he will have to “fish or cut bait.” Imagine what they are saying to one another about the manager as they wait: “What a bottleneck. He can’t make up his mind. How anyone ever got that high up in our company without being able to make a decision, we’ll never know.”

Worst of all, the manager cannot make any of these “next moves” because his time is almost entirely eaten up by meeting his own boss-imposed and system-imposed requirements. To control those tasks, he needs discretionary time, which, in turn, is denied to him when he is preoccupied with all these monkeys. The manager is caught in a vicious circle. But time is a-wasting (an understatement). The manager calls his secretary on the intercom and instructs her to tell his subordinates that he won’t be able to see them until Monday morning. At 7 pm, he drives home, intending with a firm resolve to return to the office tomorrow to get caught up over the weekend. He returns bright and early the next day only to see a foursome on the nearest green of the golf course across from his office window. Guess who?

That does it. He now knows who is working for whom. Moreover, he now sees that if he accomplishes during this weekend what he came to perform, his subordinates’ morale will go up so sharply that they will each raise the limit on the number of monkeys they will let jump from their backs to his. In short, with the clarity of a revelation on a mountaintop, he now sees that the more he gets caught up, the more he will fall behind.

With the clarity of a revelation on a mountaintop, the manager can now see that the more he gets caught up, the more he will fall behind.

He leaves the office at the speed of someone running away from a plague. His plan? To get caught up on something he hasn’t had time for in years: a weekend with his family. (This is one of the many varieties of discretionary time.)

Sunday night, he enjoys ten hours of sweet, untroubled slumber because he has clear-cut plans for Monday. He is going to get rid of his subordinate-imposed time. In exchange, he will get an equal amount of discretionary time, part of which he will spend with his subordinates to ensure that they learn the difficult but rewarding managerial art called “The Care and Feeding of Monkeys.”

The manager will also have plenty of discretionary time left over to control the timing and content of his boss-imposed time and his system-imposed time. It may take months, but the rewards will be enormous compared to how things have been. His ultimate objective is to manage his time.

Getting Rid of the Monkeys

The manager returns to the office Monday morning just late enough so that his four subordinates have collected outside his office waiting to see him about their monkeys. He calls them in one by one. The purpose of each interview is to take a monkey, place it on the desk between them, and figure out together how the next move might conceivably be the subordinates for certain monkeys that will take some doing. The subordinate’s next move may be so elusive that the manager may decide—just for now—merely to let the monkey sleep on the subordinate’s back overnight and have him or her return with it at an appointed time the following day to continue the joint quest for a more substantive move by the subordinate. (Monkeys sleep just as soundly overnight on subordinates’ backs as they do on superiors.)

As each subordinate leaves the office, the manager is rewarded with the sight of a monkey leaving his office on the subordinate’s back. For the next 24 hours, the subordinate will not be waiting for the manager; instead, the manager will be waiting for the subordinate.

Later, as if to remind himself that there is no law against his engaging in a constructive exercise in the interim, the manager strolls by the subordinate’s office, sticks his head in the door, and cheerily asks, “How’s it coming?” (The time consumed in doing this is discretionary for the manager and the boss imposed on the subordinate.)

In accepting the monkey, the manager has voluntarily assumed a position subordinate to his subordinate.

When the subordinate (with the monkey on his or her back) and the manager meet at the appointed hour the next day, the manager explains the ground rules in words to this effect:

“At no time while I am helping you with this or any other problem will your problem become mine. The instant your problem becomes mine, you no longer have a problem. I cannot help a person who hasn’t got a problem.

“When this meeting is over, the problem will leave this office precisely as it came in—on your back. You may ask for my help at any appointed time, and we will determine what the next move will be and which of us will make it.

“In those rare instances where the next move turns out to be mine, you and I will determine it together. I will not make any move alone.”

The manager follows this same line of thought with each subordinate until about 11 a.m. when he realizes he doesn’t have to close his door. His monkeys are gone. They will return—but by appointment only. His calendar will ensure this.

Transferring the Initiative

What we have been driving at in this monkey-on-the-back analogy is that managers can transfer initiative back to their subordinates and keep it there. We have tried to highlight a truism as obvious as it is subtle: namely, before developing initiative in subordinates, the manager must see to it that they have the initiative. Once the manager takes it back, he will no longer have it and can kiss his discretionary time goodbye. It will all revert to subordinate-imposed time.

Nor can the manager and the subordinate effectively have the same initiative simultaneously. The opener, “Boss, we’ve got a problem,” implies this duality and represents, as noted earlier, a monkey astride two backs, which is the wrong way to start a monkey’s career. Let us, therefore, take a few moments to examine what we call “The Anatomy of Managerial Initiative.”

There are five degrees of initiative that the manager can exercise concerning the boss and the system:

1. wait until told (lowest initiative);

2. ask what to do;

3. recommend, then take resulting action;

4. act, but advise at once;

5. and act independently, then routinely report (highest initiative).

Clearly, the manager should be professional enough not to indulge in initiatives 1 and 2 related to the boss or the system. A manager who uses initiative 1 has no control over either the timing or the content of boss-imposed or system-imposed time, thereby forfeiting any right to complain about what he or she is told to do or when. The manager who uses Initiative 2 controls the timing but not the content. Initiatives 3, 4, and 5 leave the manager in control of both, with the most significant control being exercised at level 5.

Concerning subordinates, the manager’s job is twofold. First, to outlaw initiatives 1 and 2, thus giving subordinates no choice but to learn and master “Completed Staff Work.” Second, to see that for each problem leaving his or her office, an agreed-upon level of initiative is assigned to it, in addition to an agreed-upon time and place for the next manager-subordinate conference. The latter should be duly noted on the manager’s calendar.

The Care and Feeding of Monkeys

To further clarify our analogy between the monkey on the back and the processes of assigning and controlling, we shall refer briefly to the manager’s appointment schedule, which calls for five hard-and-fast rules governing the “Care and Feeding of Monkeys.” (Violation of these rules will cost discretionary time.)

Rule 1.

Monkeys should be fed or shot. Otherwise, they will starve to death, and the manager will waste valuable time on postmortems or attempted resurrections.

Rule 2.

The monkey population should be kept below the maximum number the manager has time to feed. Subordinates will find time to work as many monkeys as he or she finds time to feed, but no more. Feeding an adequately maintained monkey shouldn’t take more than five to 15 minutes.

Rule 3.

Monkeys should be fed by appointment only. The manager should not have to hunt down starving monkeys and feed them on a catch-as-catch-can basis.

Rule 4.

Monkeys should be fed face-to-face or by telephone, but never by mail. (Remember—with mail, the next move will be the managers.) Documentation may add to the feeding process but cannot replace feeding.

Rule 5.

Every monkey should be assigned the next feeding time and degree of initiative. These may be revised by mutual consent but are never allowed to become vague or indefinite. Otherwise, the monkey will starve or wind up on the manager’s back.

Making Time for Gorillas

by Stephen R. Covey When Bill Oncken wrote this article in 1974, managers were in a terrible bind. They were ...

“Get control over the timing and content of what you do” is appropriate advice for managing time. The first order of business is for the manager to enlarge his or her discretionary time by eliminating subordinate-imposed time. The second is for the manager to use a portion of this newfound discretionary time to see that each subordinate has the initiative and applies it. The third is for the manager to use another portion of the increased discretionary time to get and keep control of the timing and content of both boss-imposed and system-imposed time. All these steps will increase the manager’s leverage and enable the value of each hour spent managing management time to multiply without a theoretical limit.

Get People On Board with Your Ideas!

Have you ever struggled to get your colleagues on board with your ideas? When facing resistance, it’s crucial to understand the underlying concerns driving their hesitation. Here are some common reasons you might meet resistance and questions to overcome them.

Have you ever struggled to get your colleagues on board with your ideas? When facing resistance, it’s crucial to understand the underlying concerns driving their hesitation. Here are some common reasons you might meet resistance and questions to overcome them.

Don't get defensive when someone resists your idea or isn’t getting it. Instead, ask for their candid reaction to understand what’s informing their position. This could sound as simple as, “How is this idea landing with you?” or “What are some specific risks that worry you?” Once you see what they’re seeing, you can present a more tailored argument—and you might even uncover some gaps in your thinking.

When the conversation becomes adversarial, when your idea is at odds with your collaborator’s, summarize and verify their points. For example: “I hear you saying that you believe X for Y reason. Is that right?” This simple strategy interrupts the point-counterpoint dynamic and makes the tone more collaborative.

When their “no” puts you in a bind. Disclose your dilemma, then pose a question that invites them to work with you to solve it. For example, “If we don’t do what I suggest, I worry we’ll run out of time and resources. How would you approach this?” Questions like these will encourage the other person to empathize with your situation and potentially lead to better ideas.

WHO NEEDS AN EXECUTIVE COACH ANYWAY?

An interesting question came up today which directly affects my career, but it occurs to me also my past. I’ll explain! Over ten years ago, I was a successful but stressed-out lawyer with no life and even less joy. This was not caused by the loved ones and friends around me but by me, and me alone!

An interesting question came up today which directly affects my career, but it occurs to me also my past. I’ll explain! Over ten years ago, I was a successful but stressed-out lawyer with no life and even less joy. This was not caused by the loved ones and friends around me but by me, and me alone!

A good friend, a successful management consultant with Accenture and other leading companies, offered me executive coaching. This was not the only time this happened. Over the years, I have met life coaches of different backgrounds and qualifications at various networking events.

I always said no, not because I questioned my friends' or other life coaches' fine qualities, but because I didn’t believe in life coaching. I could not see how it could benefit me or my life. I was arrogant, ignorant, and, on reflection, really quite stupid! This was despite the fact that I am generally considered to be quite clever and held in high regard by my colleagues and critics alike.

So, how could it be that I was such a short-sighted idiot, and what changed to make me a believer in the skill, art, and success of life coaching?

Reflecting on this, my first thought about why I had rejected coaching was that maybe it was a cultural issue. I am British by birth, and you know Brits can be a pretty proud and stubborn lot! Just look at the United Kingdom's dealings with the rest of the world, both in history and now, where, despite its reduced global influence, it continues to punch above its weight—or at least we Brits like to believe we do!

I have always been immensely proud and worked hard for everything I achieved in my career. I had some wonderful mentors along the way, not least my first-ever boss, who took me under his wing when I was a 17-year-old outdoor clerk in a law firm called Wray Smith & Co., based in the ancient heart of the British legal profession, the Inner Temple in London. I cannot tell you the love and affection I still hold for this man today. Still, there are areas where I can reflect and recognize with increased age and experience that I no longer accept or agree with many of his views, not least where it came to areas like the expression of feelings and openness to believing in these fangled new age practices that have never helped anyone.

As a successful lawyer and, subsequently, a judge, I wanted to be like him, and for a long time, I believed his every word. Please don’t get me wrong; it was not that he was incorrect; it was just a very different age born of the Second World War, as well as the period after that, which were tough times in the United Kingdom and the rest of Europe for people of my parents and grandparents generations. So, was this a cultural issue that was responsible? I think it contributes to it, but it is not the only issue.

Was I a coward? I don’t mean in the old-fashioned sense of the expression! I have always tried to face any problem head-on and work hard to find a solution rather than avoiding it! That’s a contradiction to accepting the benefits of executive coaching, RIGHT?

So, what was I afraid of opening up? Admitting I have made mistakes and facing them? I think if we are honest with ourselves, we are all a little fearful of doing so; that is what makes us human after all, unless, of course, you are a sociopath, a few of whom I have worked for over the years, in which case your self-belief and confidence is second to none!

The thing is, and it’s a silly but essential thing, COACHING WORKS! Not only does it work, but it is not about mistakes or leaving yourself feeling like you are exposing yourself. It is about the future as well as the here and now!

When I work with a client, the client sets the agenda and comes up with the answers, albeit with a bit of steering and guidance from me using my ears, eyes, and mouth, asking the right questions. My clients already have the answers, but they can be hidden deep or right in front of their eyes! I help them find them; as I said, COACHING WORKS!

As a professionally trained life coach, I am delighted when I see my clients' breakthroughs and fantastic results. Knowing that they are progressing to the next stage of their success or breakthrough in life brings me genuine pleasure and joy.

I shouldn’t be surprised; as soon as I started using a coach, the old concerns and negative thoughts were there, and I was initially hesitant, resistant, and nervous. My skillful coach asked me the right questions, and pretty much straight away, I noticed my life changing for the better through several breakthroughs.

I realized that events or thoughts that had held me back for years were not the roots of my problems; it was me and only me! I learned to become a happier, better, and more successful person.

So, all those years ago, how could I have been so unwise as to believe that coaching could not help me? Change my life for the better, both professionally and personally? I’m still unsure if I have an answer to that, but I have learned that coaching is about a brighter future and improving the here and now! That is all that matters!

Professionally trained life coaches undertake specialist courses and obtain skills as part of their accreditation process required by the International Coach Federation, of which I am a member. This process involves them learning about themselves to enable them to help others. It is a fascinating journey, sometimes tricky, but extremely rewarding.

Why wouldn’t this be attractive? Is it cultural or more? Only you can find out the answer to that question, but trust me, I wouldn’t have missed this journey for anything. I’m so happy that I can say out loud that I am an ICF COACH, able to help others on their journey, too!

To Be Or Not To Be, That Is The Question. Whether 'Tis Nobler In The Mind To Suffer!

Well, that’s a bit deep and very Shakespearean, but if you think about it in its most straightforward interpretation, what do we want to be? We start life being molded by the influences around us, whether family, peers, society or especially society!

Sometimes, we have it impressed upon us by well-meaning people to study hard, work hard, get our qualifications, work harder, buy property, get attached, get a family, work even harder, suffer even harder, repeat, and then retire, unless, of course, you shuffle off your mortal coil (even more Hamlet) before then from all that hard work!

So, are there different approaches we can use to learn about life? I remember a close friend of mine encouraging her child to engage in circus workshops and pursue non-academic activities. She’s nuts, I thought. So, the kid isn’t very academic, but it indeed makes sense to keep pushing them academically so they can make something of their life!

Wow, was I such a short-sighted person? As a result of my friend’s foresighted approach, her child, one of my Godchildren, learned structure and discipline while having fun. They are now a highly respected physicist, but that’s irrelevant. They could have become anything because their parents thought outside the box and allowed them to do something they wanted, which gave them arguably the same strong foundation as any tutor or academic could have done, but differently!

So that takes me back to my original point, “To Be Or Not To Be!”

Is it too late to review your life, reinvent yourself, and have the one you desire whilst still being successful?

My simple response to that question is, "Why not?" I changed my country of residence at 45 and my career at 48!

You tell me why it isn’t possible, and I’ll likely help you discount each and every one of those “excuses.” That, after all, is usually what they are! Is it possible that we fail to see possibility because we are determined to remain in our comfort zone, denying ourselves a place where a happier and better existence lives?

Did you ever stop for a moment and ask yourself what you want? Maybe it’s time you did that and looked for possibilities rather than the reasons why you can’t succeed!

To be or not to be: That is the question. You have the answer, but you might need help finding it so call me!

Well, that’s a bit deep and very Shakespearean, but if you think about it in its most straightforward interpretation, what do we want to be? We start life being molded by the influences around us, whether family, peers, society or especially society!

Sometimes, we have it impressed upon us by well-meaning people to study hard, work hard, get our qualifications, work harder, buy property, get attached, get a family, work even harder, suffer even harder, repeat, and then retire, unless, of course, you shuffle off your mortal coil (even more Hamlet) before then from all that hard work!

So, are there different approaches we can use to learn about life? I remember a close friend of mine encouraging her child to engage in circus workshops and pursue non-academic activities. She’s nuts, I thought. So, the kid isn’t very academic, but it indeed makes sense to keep pushing them academically so they can make something of their life!

Wow, was I such a short-sighted person? As a result of my friend’s foresighted approach, her child, one of my Godchildren, learned structure and discipline while having fun. They are now a highly respected physicist, but that’s irrelevant. They could have become anything because their parents thought outside the box and allowed them to do something they wanted, which gave them arguably the same strong foundation as any tutor or academic could have done, but differently!

So that takes me back to my original point, “To Be Or Not To Be!”

Is it too late to review your life, reinvent yourself, and have the one you desire whilst still being successful?

My simple response to that question is, "Why not?" I changed my country of residence at 45 and my career at 48!

You tell me why it isn’t possible, and I’ll likely help you discount each and every one of those “excuses.” That, after all, is usually what they are! Is it possible that we fail to see possibility because we are determined to remain in our comfort zone, denying ourselves a place where a happier and better existence lives?

Did you ever stop for a moment and ask yourself what you want? Maybe it’s time you did that and looked for possibilities rather than the reasons why you can’t succeed!

To be or not to be: That is the question. You have the answer, but you might need help finding it so call me!

Let your employees know they count, and show them you respect them!

Treating everyone with respect is the foundation of good leadership. But what does respectful leadership actually look like in practice? Here are some behaviors to prioritize.

Treating everyone with respect is the foundation of good leadership. But what does respectful leadership actually look like in practice? Here are some behaviors to prioritize.

• Build trust. This requires three factors: developing positive relationships, sharing knowledge and expertise, and consistently treating people.

• Value diversity. Hire team members from diverse backgrounds, check your unconscious biases, encourage perspectives that challenge the status quo, and, of course, treat everyone equally.

• Stay attuned to your employees’ emotions. You can’t be aware of everything your team members are going through in their personal and professional lives. But you can—and should—convey that you’re there for them should they want to discuss sensitive issues or concerns.

• Balance compassion and accountability. Establish a culture that supports work-life balance, and make it clear that productivity shouldn’t come at the cost of your employees’ well-being.

• Resolve conflicts. Don’t take a hands-off approach when tensions arise on your team. A respectful leader willingly engages in conflict resolution.

• Give constructive feedback—productively. Be direct and honest about your employees’ strengths and weaknesses. Ignoring or minimizing either is ultimately unkind, counterproductive, and disrespectful.

Do You Have the Skills You Need to Be the Boss?

Do You Have the Skills You Need to Be the Boss?

Transitioning into management for the first time can be a significant career milestone for many people. Identifying which skills you might need to develop before leaping will be helpful for any potential leadership shift. Ask yourself these five questions:

Transitioning into management for the first time can be a significant career milestone for many people. Identifying which skills you might need to develop before leaping will be helpful for any potential leadership shift. Ask yourself these five questions:

• What’s my leadership style? Reflect on your strengths, personality, and values, then decide what you want to be known for. Remember, you can adapt your approach over time as you continue to learn and advance.

• How will I help my team grow? Understanding how to measure performance and assess gaps and growth opportunities on your team will be essential in your role as a manager. Take time to think about how your promotion may impact team structures and dynamics.

• How will I prioritize and delegate work effectively? Ask yourself what you’d need to stop doing, keep doing, and do more of—and how you’ll provide oversight and accountability for the work you assign to others.

• Am I an excellent public speaker, and can I lead meetings? Do an honest appraisal of your communication skills and assess your comfort with leading meetings and presenting to larger groups.

• Am I comfortable delivering feedback and resolving conflict? Providing helpful direction, addressing performance gaps, and solving interpersonal problems are essential managerial responsibilities. Consider issues you may have witnessed with coworkers regarding processes, projects, or interpersonal dynamics. What did you learn from what you observed?

Defuse the Simmering Resentment on Your Team

If you’ve noticed an uptick in subtle digs and snarky comments on your team, it may indicate a deeper issue: simmering resentment. As a leader, you must restore harmony before it’s too late.

If you’ve noticed an uptick in subtle digs and snarky comments on your team, it may indicate a deeper issue: simmering resentment. As a leader, you must restore harmony before it’s too late.

Start by paying close attention to team dynamics—and if you see something, say something. Don’t assume issues will be resolved independently—instead, open lines of communication, preferably one-on-one. Show genuine interest in your team member’s well-being and allow them to express their thoughts and feelings. A simple “How’s everything going?” can lead to deeper conversations.

Remember that resentment may be directed at you. If that’s the case, don’t get defensive. Instead, seek feedback with curiosity. Your openness can defuse tension and rebuild trust. If you find your team’s frustration with the organization, listen to their perspectives, support their needs, and advocate for them (to the best of your abilities).

Finally, resentment can surface during routine meetings or communication, so shake things up. A walking meeting or an experiment with rotating leadership roles can reset negative communication patterns and create new dynamics. Focusing on common goals and proactively celebrating wins can shift the team’s energy from conflict to collaboration.

Simplify Your Strategy

Many organizations confuse operational plans with strategy. Creating a strategy is an outward-looking, relatively high-level exercise about identifying how to meet your stakeholders’ needs. Once you’ve done that, you can figure out the specific steps you need to take to get there. Here’s how to build a strategy that avoids fragmented efforts and missed opportunities.

Many organizations confuse operational plans with strategy. Creating a strategy is an outward-looking, relatively high-level exercise about identifying how to meet your stakeholders’ needs. Once you’ve done that, you can figure out the specific steps you need to take to get there. Here’s how to build a strategy that avoids fragmented efforts and missed opportunities.

Separate strategy from action. Strategy is about positioning your business in the marketplace—it’s not a list of tasks for each function to execute. When you confuse strategy with action, you and your team will lose sight of the overall direction. Keep strategy focused on big-picture positioning instead and let specific decisions and deliverables follow.

Reframe your language. The words you use shape your thinking. Replace terms like “marketing strategy” with “customer strategy” and “HR strategy” with “employee strategy” to focus on your stakeholders. Subtle shifts like this help ensure that your strategy remains aligned with the needs of the people you’re serving, not just internal functions and processes.

Are you a workaholic?

Are you a workaholic? I know without hesitation that I used to be when I worked as a lawyer in the City of London. I would get into the office early and leave later than most people. Even when I got home, I would not switch off. I was embarrassed once when I was contacted by the company that provided our management software, as I had been the only lawyer in the United Kingdom to log on during Christmas Day. They wanted my permission to mention it in an article! It is fair to say I received some ridicule from colleagues who saw the piece when it was published….. Honestly, like any addiction, I miss it and some days, I still feel that urge coming back.

Are you a workaholic? I know without hesitation that I used to be when I worked as a lawyer in the City of London. I would get into the office early and leave later than most people. Even when I got home I would not switch off. I embarrassingly once got contacted by the company that provided our management software, as I had been the only lawyer in the United Kingdom to log on during Christmas Day and they wanted my permission to mention it in an article! It is fair to say I received some ridicule from colleagues who saw the pice when it was published….. Honestly, like any addiction, I miss it and some days, I still feel that urge coming back.

Workaholism isn’t about how many hours you work—it’s about your ability to disconnect from your job. Arguably, it is a survival mechanism that deals with insecurities or the need to be successful. To help determine whether you might be a workaholic, read the following statements and rate the degree to which each one describes you using the following scale: 1 = never true; 2 = seldom true; 3 = sometimes true; 4 = often true; 5 = always true.

1. I work because there is a part inside me that feels compelled to work.

2. It is difficult to stop thinking about work when I stop working.

3. I feel upset if I have to miss a day of work for any reason.

4. I tend to work beyond my job’s requirements.

5. Vacations are uncomfortable, and I feel guilty for taking the time off.

Add up your total score. If you rated any of these items a four or a five, you have some workaholic tendencies. But if your total score is 15 or above, you’re displaying significant signs of workaholism. I can help you to find different strategies to help you find balance.